Luis Dias

I was honoured and privileged to be invited to present a paper at the National Conference on ‘The contributions of the Goan Christian musicians to the musical heritage of Goa’ earlier this month at the Thomas Stephens Konkani Kendra (TSKK) Porvorim, organised jointly by TSKK and the Goa Government Department of Gazetteer and Historical Records.

My given topic was ‘Contributions of the Goan Christian musicians to western classical music and the diaspora.’

Writing the paper within the limits of a finite word-count proved challenging, but also helped keep it taut and focussed.

One spin-off from the Portuguese colonial presence in Goa (the longest on the Indian subcontinent compared to other European powers) has been the introduction of western music as part of its evangelisation. The seminaries, but more importantly the village parish schools, were where this instruction happened.

Much is made of the gushing praise in the 1660s by a visiting Monsignor Giuseppe Maria Sebastiani on hearing sacred music performed at the Bom Jesus Basilica and his observations about music at religious services in the villages. It is cited whenever one wants to invoke a hallowed past for western music in Goa, and extrapolate from there a seamless glorious lineage to our present, which has also to be gushingly exalted, even when the truth is quite audibly often far from glowingly praise-worthy. All one achieves by this extrapolation is to engender complacency and sloth.

In fact, sifting through primary and secondary sources one gets only a sketchy picture of the state of music in the intervening centuries to the nineteenth century, and the emphasis has largely been on vocal sacred and folk music, much less so on (‘non-sacred’) classical music.

Reading through history of the inexorable decline of the fortunes of the Estado da ĺndia for a whole host of reasons, and the later suppression of the religious orders, one shouldn’t be surprised that music was one facet of the larger pattern of neglect and decay. It was the bleak employment prospects that prompted Goans to migrate in the first place.

It makes the achievements of our Goan musicians upon migration elsewhere on the Indian subcontinent and much further afield (as highlighted throughout the above-mentioned conference) all the more commendable. Being able to read and even write music, and to play a musical instrument to even a modest degree, could in effect be a ticket to a better life wherever they went.

As far as western classical music goes, Goans (sometimes written as ‘Goanese’) have a significant presence in every aspect from pedagogy, instrument repair and sales to performance in the furthest reaches of our subcontinent, including what are today Pakistan, Bangladesh, even Myanmar.

Ever since orchestras began to form in our part of Asia in the early twentieth century, Goan-origin musicians have continued to be part of the rank and file of all orchestral and chamber ensembles. Sometimes they were even at the helm. Goan-origin barrister, virtuoso violinist and conductor Vere da Silva formed India’s first string quartet in the 1940s, and the Bombay City Orchestra a decade later, notably conducting American contralto Marian Anderson’s 1957 goodwill visit concert in 1957.

But here’s the blunt truth that leapt out at me as I researched this paper: Every home-grown Goan musician, past and present, who has attained world-class training and exposure, has had to travel beyond Goa’s borders to achieve this. However, those born into Goan-origin families in overseas milieux more nurturing to classical music have scaled great heights. One prominent example is Canadian Goan conductor Jordan de Souza, who at 36 is First Kappellmeister at the Komische Oper Berlin, a post he has held since 2017.

I also came upon uncomfortable truths and questions posed by eminent musicologist, composer and conductor Rev Fr Lourdino Barreto way back in 1982 about the state of classical music in Goa. He minced no words then, and 42 years later, it has actually gotten much worse.

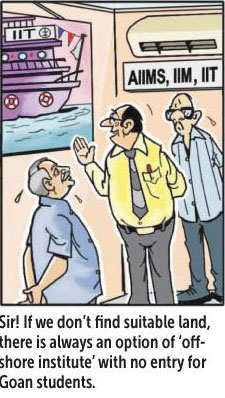

Goa, the crucible of western music, has through inertia fallen far behind not just India’s big cities, but even Nagaland.

We lack even one public (private closed-door spaces don’t count), decent purpose-built acoustically-flattering performance venue for classical music, with an in-situ grand piano. It means Goa gets bypassed when any great performer plans their India concert tour.

Goan-origin world-renowned soprano Patricia Rozario’s laudable Giving Voice to India (GVI) initiative ironically encountered the most resistance (hostility, even! I know this first-hand) to uptake here in Goa, but has thrived elsewhere in India. But now Goa spends ludicrous amounts of money to repeatedly fly in GVI soloists from elsewhere when we could so easily have had the same calibre singers here! Instead, our adults and youth prefer to literally play second fiddle, or skulk behind stronger singers in safety-in-numbers mammoth choirs instead of doing the much harder work of fostering grass-roots music education, for voice, and for music in general.

In my own youth, orchestral initiatives had, as late as the mid-1990s, the full complement of upper and lower strings, all the woodwinds and brass, all played by home-grown Goans. Today such forces are unimaginable. Even violists, cellists and double-bassists are parachuted in from outside the state, and the brass and woodwinds are dispensed with, or compensated for by piano reductions, or the repertoire requiring them avoided altogether.

This has severely limited and impoverished the exposure that our public, especially our youth, have to a huge swathe of the classical music repertoire, and in the absence of role models playing the now rarely-seen-or-heard instruments it is a downward spiral.

But Goa gets deluded by all the crony media hyperbole into believing ‘All Is Well,’ to quote the ‘3 Idiots’ catchphrase. A falsehood, repeated ad nauseum, is accepted as fact.

We can turn this around, however. Music pedagogues from all over want to help us build a solid foundation for music education, from grass-roots to the highest global-standard conservatory level. It is already happening elsewhere in India. It’s now or never for Goa.

(Dr Luis Dias is a physician, musician, writer and founder of Child’s Play India Foundation)